The fact that many men lose their Y chromosomes as they become older has been recognised for more than half a century. However, no one was sure whether it made a difference. For example, grey hair is a symbol of old age, but it has no clinical significance.

Researchers, on the other hand, now say it matters. It means a lot to me to hear that.

Y chromosome deletion in male mice gives fresh knowledge, according to a recent research. When the Y chromosome was removed from these mice’s blood cells, scar tissue formed in their hearts, leading to heart failure and a shorter lifespan, according to a study published in Science on Thursday.

Because the loss of Y was linked to the mice’s ageing diseases, the research suggests that the same thing may happen in human males as well. Research after study has shown an increase in the risk of chronic illnesses like heart disease and cancer in those who lose the Y chromosome. Researchers at Science believe that the loss of Y might even explain part of the difference in life expectancy between men and women.

Other researchers who weren’t involved in the project were impressed.

Dr. Ross Levine, deputy physician in chief for translational research at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, remarked, “The writers absolutely got it here.” “It’s a critical piece of work.”

An encounter with an ex-colleague on the bus in Sweden inspired new study at Uppsala University, according to Lars Forsberg, one of the researchers involved in the project. After a few minutes of discussion, the professor informed Dr. Forsberg that fruit fly Y chromosomes had a greater role to play than previously thought.

He was curious, too. He’d never given the disappearance of Y chromosomes much thought. Nearly of the genes needed by male cells are found on the X chromosome, which has just one X and one Y (females have two Xs). It had long been accepted that the Y chromosome was a genetic wasteland, and Dr. Forsberg had agreed.

Male blood cells lose their Y chromosome in around 40% of older men. At least 57% of those who reach the age of 93 have lost part of it.

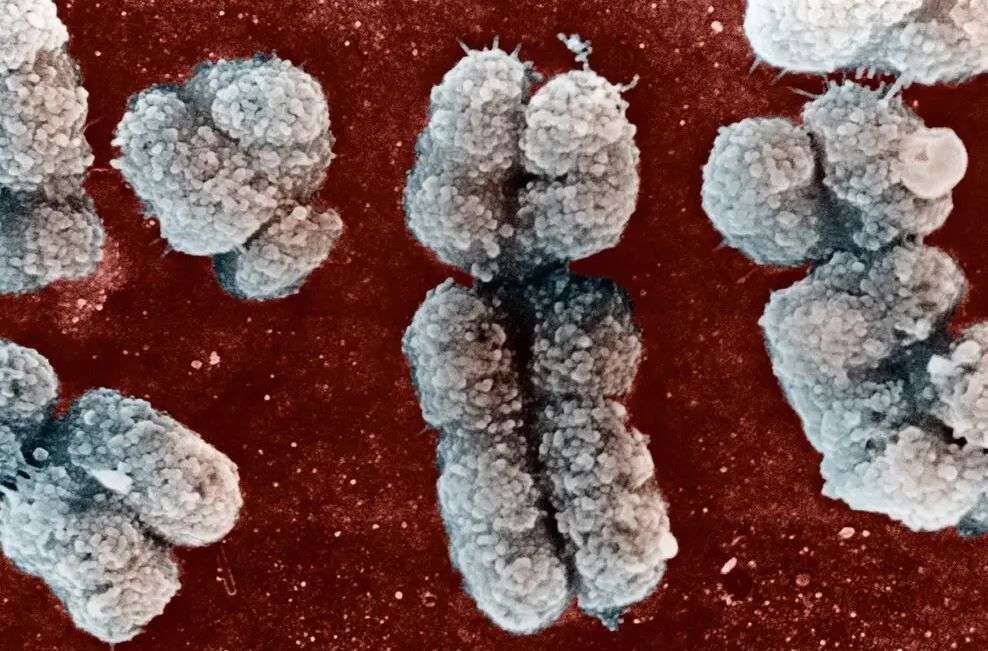

During cell division, the chromosome is thrown out of certain blood cells and eventually disintegrates. The end outcome is a loss of Y in a mosaic pattern, according to the findings.

Other than quitting smoking, there is no method to lessen the likelihood of losing a Y chromosome. While testosterone levels decline with age, this is not the cause of the problem. The effects of low testosterone would not be mitigated by using testosterone supplements.

Dr. Forsberg returned to his computer to investigate the theory put out by his professor and found data on 1,153 elderly men from the Uppsala Longitudinal Research of Aging Men, a significant Swedish study.

Dr. Forsberg stated, “I received the data in a few hours and I was like, ‘Wow.'” The average life expectancy for males who have had a significant reduction of Y chromosomes in their blood is 11.1 years.

When I heard it, I couldn’t believe it. “Of course, everything was redone.”

It was confirmed by an article he published in 2014 in the journal Nature Genetics, which showed that decreased levels of the Y chromosome in blood cells were linked to higher mortality rates and cancer diagnoses.

As soon as he started Cray Innovation, he became a stakeholder and formed the firm to test men for the loss of Y.

Other researchers started to publish similar findings as a result of this. The loss of the Y chromosome in blood cells was soon linked to heart disease, shorter lifespans and numerous age-related disorders such solid tumours and blood malignancies, according to around 20 independent research.

Dr. Forsberg then received a call from Kenneth Walsh, the head of the University of Virginia School of Medicine’s Hematovascular Biology Center. As a result of his work on CHIP, Dr. Walsh became interested in the loss of Y chromosomes as a result of an increase in cancer mutations in blood cells. CHIP patients have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer, thus Dr. Levine established a CHIP clinic at Sloan Kettering.

Those with Turner syndrome are unique. Women with the disease are at risk for cardiovascular irregularities and non-ischemic heart failure, much like males who have lost their Y chromosomes. Women with two X’s have a lower life expectancy than women with one X.

It’s too early to determine what men can do to prevent or lessen the repercussions of losing their Y chromosomes other than to cease smoking.

Dr. Walsh’s team discovered that inhibiting TGF-beta, a critical chemical involved in the development of scar tissue, might preserve the hearts of mice lacking Y chromosomes.

According to National Cancer Institute head of cancer epidemiology and genetics Dr. Stephen Chanock, the research on mice was “very remarkable.” However, he cautioned that there is currently no proof that TGF-beta inhibitors may help males who have lost their Y chromosome.

Dr. Chanock also expressed concern about the “over-interpretation of this data for monetary goals,” saying, “I am profoundly concerned about the misuse of these data.”