The World Health Organization (WHO), in response to concerns that the phrase “monkeypox” conjures up racial stereotypes and stigmatises victims, is suggesting that the name of the illness be changed to mpox. This is because of the objections. The two designations are going to be used interchangeably for the next year, until monkeypox is finally eradicated.

Following outbreaks that started around six months ago in Europe and the United States, the advice was released on Monday. These outbreaks prompted significant worries that the infection may spread broadly throughout the world.

The virus had been quietly circulating in rural parts of Central Africa and West Africa for decades, but in recent months, the majority of those who contracted the disease were men who had sex with men on other continents. This has compounded the stigma that has been placed on a community that has been burdened for a long time by its association with AIDS.

A review that lasted many months and included feedback from members of the general public as well as specialists from all around the globe led to the selection of the new name.

Because monkeys are not involved in the disease’s transmission in any significant manner, its common name, “monkeypox,” has always been rather misleading.

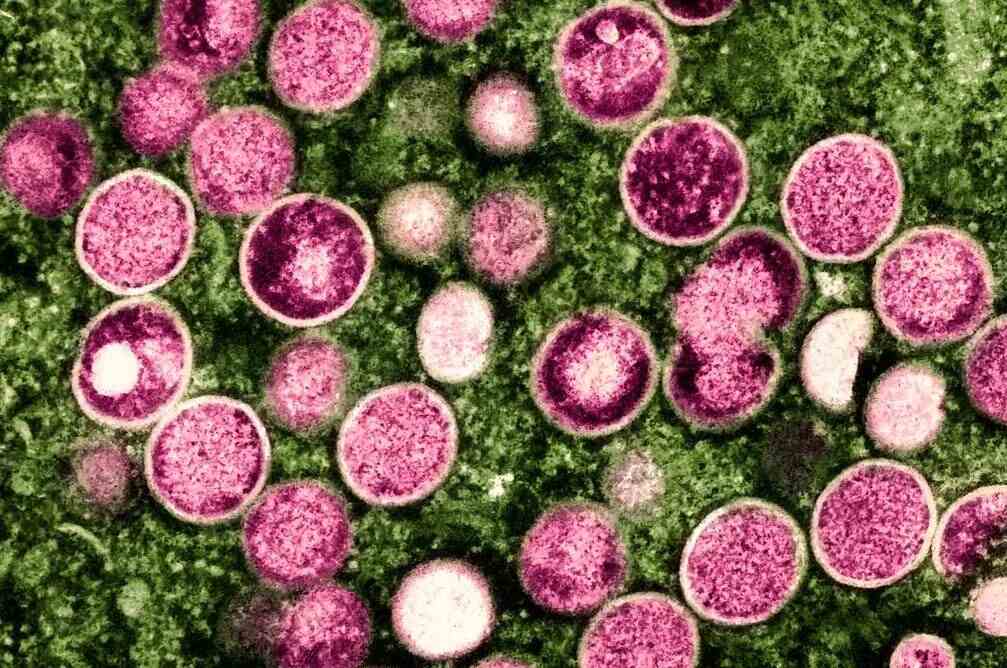

More than half a century ago, when the virus was initially discovered by scientists, it was in a colony of lab monkeys that were confined in cages in Denmark. This is where the term came from. New standards for giving names to infectious illnesses have been advocated for by the World Health Organization (WHO) since 2015. The suggestions include that names should “avoid causing offence to any cultural, social, national, regional, professional, or ethnic groups,” as well as “prevent needless negative impacts on travel, tourism, or animal welfare.”

Some people believed that the outbreak of monkeypox only served to strengthen negative Western ideas about Africa being a source of disease and sexually transmitted infections. Some of its detractors said that it perpetuated racial prejudices that are firmly ingrained in American society and that equate black people to apes.

In an open letter, Dr. de Oliveira and twenty other African experts expressed their concern that attempts to manage the illness would be hampered if a nomenclature that was less challenging could not be determined.

Critics have also taken issue at the media’s depiction of the epidemic, pointing out that some Western sites had first chosen photographs of lesion-pocked Africans to represent an illness that was virtually completely afflicting white males.

Human-to-human transmission in Africa was very rare until to the epidemic that occurred this year. The majority of cases occurred in rural regions among individuals who had direct contact with wild animals. The condition may produce very high fevers, itchy rashes, and painful sores, although it seldom results in death.

The ongoing reference to and naming of this virus as African is not only erroneous in the context of the present worldwide pandemic, but it is also discriminatory and stigmatising, according to the letter.

There will be some trace of the term monkeypox left behind. According to the World Health Organization, it will continue to be searchable in the International Classification of Diseases, which will make it possible to have access to historical material on the illness.

In spite of its highly publicised introduction in both the United States and Europe, mumps has largely lost its status as a severe hazard to public health as the number of reported cases has significantly decreased.

Since the epidemic was initially reported in the spring of 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report that there have been a total of 28,248 cases and 14 fatalities. In August of last year, there were more over 400 cases recorded; in November, there were only around a dozen or so instances reported per day throughout the nation.

At the end of the day, the infectious agent was only found in a certain subset of the population, namely homosexual and bisexual males who had several relationships.

Because the virus needs close contact to spread, it is easier to contain than its more lethal and transmissible viral cousin, SARS-CoV-2. This drop in new infections has been linked to a shift in sexual behaviour, the widespread availability of vaccines, and a sort of lucky break: the virus requires close contact to spread.