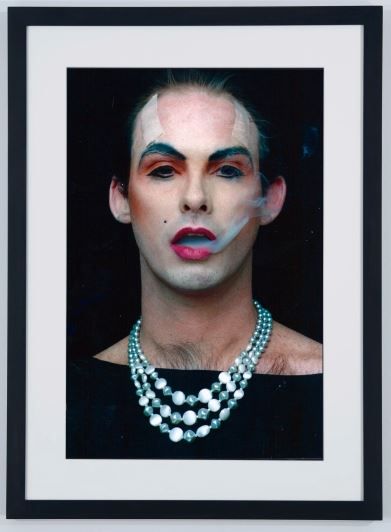

Hunter Reynolds, a 30-year-old artist in New York City at the time, was helped one night in 1989 by a friendly drag queen to get dressed up at home. With his gorgeous features adorned and converted into an androgynous cabaret star in Berlin during the Weimar years, the results were fascinating to him. He donned a tweed coat and went to a number of art-related functions. He claimed to be a Los Angeles-based performance artist so that his friends wouldn’t identify him.

Throughout his life, Mr. Reynolds has been fascinated with gender and its boundaries and potential. When Larry Kramer and others founded ACT UP as a grass-roots anti-homophobia protest group, he was on the front lines of the fight against the disease that would eventually kill him, as well as against the homophobia in politics, healthcare, and in the art world that made the fight so much more urgent. In the future, he would devote more time to creating work that centred on his physique.

Patina du Prey, his alter persona, was born soon after. Full-skirted antebellum dresses in satin, organdy, and taffeta with stiff bodices tailored to Mr. Reynolds’s very manly body showed off his hairy chest and strong arms for Patina were created by Mr. Reynolds. As Patina’s performances progressed, the costumes became increasingly ornate.

Patina wore blue taffeta and hung from a cage in a gallery for hours at a time in an early piece. While guests nibbled on food from a banquet laid out on a naked man, women in maenad costumes read feminist texts aloud from feminist books, he swayed slowly, like a music box ballerina, in a white satin gown printed with images of drops of his blood and the hair of his collaborator, Chrysanne Stathacos. A 1951 Surrealist work by Meret Oppenheim, “Spring Feast,” was the inspiration for this piece by Mr. Reynolds and Miss Stathacos, but whereas that work placed its food on a nude woman, they explicitly served theirs on a male.

In 1993, Reynolds created a black satin gown with the names of 25,000 AIDS victims from the AIDS Quilt catalogue as a living tribute. Patina was the highlight of the show. It was a moving experience when Mr. Reynolds first displayed it in a Boston exhibition, whirling for hours on a pedestal as he was known to do.

Reynold’s death was announced on June 12th at his Manhattan residence. He had reached the age of 62. P.P.O.W. gallery co-founder Wendy Olsoff, who was diagnosed with an aggressive type of squamous cell cancer, blamed it on the gallery’s exposure to sunlight.

When Anne Pasternak, a former director of the public art group Creative Time, teamed with Hunter Reynolds in 1994 to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Stonewall, she stated, “Hunter wore his grief and his sorrow, and he did it with honesty and elegance.” Throughout Manhattan, Mr. Reynolds wore the outfit, removing the bodice on the steps of the New York Public Library’s main branch.

While curating his work at a gallery in Hartford, Conn., Ms. Pasternak met Mr. Reynolds and performed as one of the maenads in “The Banquet.”

In a phone conversation, she claimed, “He didn’t disguise his H.I.V. status.” In particular, he encased his virus-infected body in the Memorial Dress and surrounded himself with it.” At the time, I don’t believe I really grasped how gutsy that was.

He said, “Don’t you dare turn your back on me.” You couldn’t look away from it. ‘This is me.’ he said, twirling on his stage. ‘We are this.'”

Robert and Danielle (Dusseau) Reynolds welcomed their first child, Hunter Wayne Reynolds, on July 30, 1959, in Rochester, Minnesota.

Hunter was seven years old when his parents split. He travelled from Florida to California at the age of 15 to live with his father, an actor who was out of work and unable to find a job.

When he wasn’t working as a lifeguard or an accountant, Hunter performed as a disco dancer or an insurance company’s mailroom. Soon after graduating from the Otis Art Institute, where he received a B.F.A. (with honours) in 1984, he relocated to New York City to pursue his career as an illustrator at the Parsons School of Design (now the Otis College of Art and Design).

The ACT UP affinity group, which Mr. Reynolds founded, consisted of activist artists who used fliers, artwork, and other actions to protest the Helms AIDS Amendments, sponsored by conservative Republican senator Jesse Helms and prohibiting federal funding for AIDS education. Such spinoffs were known as the ART + Positive affinity group.

Additionally, Mr. Reynolds performed a series he dubbed “Mummification” in addition to Patina’s antics. The more difficult activity required wrapping him in plastic wrap and taping him to a loading cart or placing him in a gallery or public park, where attendants would then cut off his skin and let him free.

He also produced two-dimensional work: As part of his “Survival AIDS” project, he used photos of his own work, blood spatters, and other material to weave together stories on AIDS from The New York Times.

Everywhere she went from Muscle Beach in Santa Monica to Berlin’s Metro, Patina twisted her way through history. She was frequently seen dancing with passers-by while clad in a spinning dervish-bride hybrid of tulle. In an extended eight-year partnership dubbed “I-Dea The Goddess Within,” photographer Maxine Henryson shot these photographs.

Linda Kirkland Gallery, New York, had a solo exhibition of their work in 1997. Patina’s white garment, which Holland Cotter of The New York Times described as “as though frozen in mid-curtsy and ringed by an aureole of dried flowers,” was also on display as part of the exhibition. ‘The symbol of a cheerful but politically incisive performance about emancipation still very much in process,’ he said.